I’ve been working on some of my poems this morning, and an overwhelming sense of gratitude keeps pulling my attention from the page, so it is time to express that gratitude. Until recently, I had never submitted my poems for publication. But I recently did begin to submit them, and I have had more success getting them published than I ever expected, and that is really due to my taking to heart the support of a very few people from my past.

|

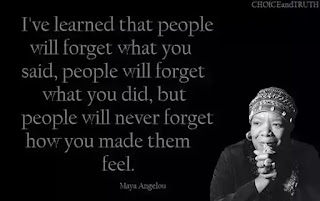

| Sister Sal, upper right at the end (around the time we had the argument!) (that's me, center in front of my mother) |

me (rest her soul) a lesson against plagiarism, but instead gave me a different lesson - that there was

something worthwhile about what I’d written. Love you, Sal.

That lesson was reinforced when I was in graduate school. My main Masters’ advisor - the wonderful amazing Nicola Morris - was constantly reaffirming the poetry I sent her. She could be brutal with her feedback, but always, always it was underscored with careful thoughtful advice that was infused with her deep desire to see you succeed in getting where you were trying to go. I loved her then, and always will. I would wait with no small anxiety for the package each week containing her critiques, and

they would always send me back to my keyboard with excitement and energy to GET THERE. And, when she liked a poem as I had submitted it, her comments could send my spirit flying for days. My favorite was a comment scrawled in an upper corner of one poem that simply read: “Lovely, lovely, lovely.”

So why didn’t I send poems in for publication until all these years later? That is due to another, considerably less appreciated, person from my past, my fourth grade teacher, Sister Something-Or-Other (I think I’ve forgotten her name out of revenge). She would take student writings from our English class and call us up to her desk in front of the rest of the class for her to comment on them. I will never forget the day I had turned in an essay about the men and women of the working-class neighborhood where I lived then, and she called me up.

She looked at me, down at my paper in front of her, and then stared out the window at the back of the classroom as she said: “You are a very good writer - it’s just too bad you don’t write about anything important.”

That comment never left me. If there is anything a writer wants, it’s for those who read the words we've written to feel that they are in at least a small way, important. Her words did not stop me, over the years, from submitting stories, essays, and, finally, a novel even after I'd received buckets full of rejections. But never poetry. I’d had three poems published, but submitted by teachers of mine, not by me. Why could I submit all these other writings and not my poetry?

Because, what it took me years to realize is that poetry, at least for me, is the heart of everything. Damn near everything I’ve ever written began with an idea expressed in a poem, and sometimes some

language from a poem made it into essays or stories or novels. Once, in a review of my novel “Somewhere Never Traveled” the person reviewing wrote “J. McKenzie must be part poet….” Few comments I’ve ever received made me smile so broadly.

Someone once said that poetry is the art of levitation - meant to uplift the reader, to take us somewhere that feels above the normal world, so that we can see clearly. I think most fiction writers feel that any writing should fit that - that we always aim to touch the most basic essence of humanity in the reader, and make it stronger. That, dear sister I-Don’t-Remember - is IMPORTANT.